A Bachelor's Cupboard (1906)

Written by A. Lyman Phillips, Traveler, Gourmand, Aviator...Lady.

A Bachelor’s Cupboard: Containing Crumbs culled from the cupboards of the great unwedded written by A. Lyman Phillips caught my eye right away. Honestly, who can resist this title? I immediately want to know what kind of a man might be dishing up such a cookbook in 1906. I pledge to relentlessly stalk him through the old newspapers and dig up all the dirt. But first, it’s time to eat. I dive into the text on the web where I can peruse it free of charge. It has loads of beautiful recipes next to delightful illustrations by Will Jenkins. Chapters include Being a Bachelor, Snacks of Sea Food, Bachelor Bonnes Bouche, A Dissertation on Drinks, and so much more.

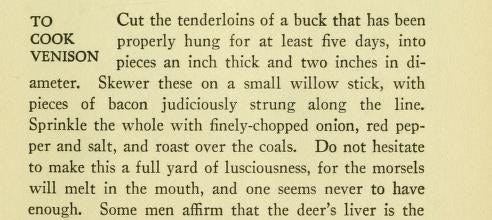

What am I in the mood for, though? Perhaps Boston beans or a roast fowl? Perhaps cheese sandwiches or deviled kidney? Would I rather a sip of Earthquake Calmer or an English Punch? Do I want it all? Well, maybe not the kidney, but otherwise, I’m intrigued. Finally, I spot a preparation for venison. In fact, it would be a good way to use some that’s stocked up in the freezer. It always arrives at the house during hunting season, but I don’t lean toward it as quickly as chicken or steak or sausage. Besides, this recipe looks damn delicious. A. Lyman Phillips instructs on the preparation of venison in this way:

I love that recommendation. A full yard of lusciousness. Honestly, who is this guy? I’m ready to find out.

In the meantime, I thaw the venison as we run into the hustle and bustle of a busy weekend. By the time I get a chance to skewer and prepare the goods it’s Sunday evening. I prep the fire early allowing it time to burn down. My son works on an art project while my husband paints and replaces a base board. I fiddle with a puzzle and read. Once the sun has set and the fire has been going for an hour or two, I weave the bacon in between the pieces of venison and call it good. My fire has pretty well burned to coals as I haphazardly rearrange the logs and place a grate between them. As I lay the skewers on the grate, and nestle pepper and onion over the top, a lovely sizzle erupts.

I want to tell you that the house fills with luscious and heavenly aromas as the drippings hit the fire, that people knock on my door drawn by the smells drifting from our chimney. Friend, that is not the case. Here’s what really happens.

My two ailing dogs haven’t been eating their meals well. So my son, who is 10, decides he will make them a special dish so they don’t starve. He grinds up their dog food to make a sort of flour and then adds some egg, peanut butter, and milk. He stirs it into a batter and forms it into a large cookie which is inserted into the oven at the same time that I place these precious skewers over the fire. Have you ever cooked dog food before? No? Ok, well, it smells pretty much how you can imagine it would smell. Like dog food.

With dog dinner securely in the oven, my son is alerted to what I’m doing and hoverboards into the living room to deliver an apple dusted in cinnamon and sugar. I, an ill prepared over-the-coals middle aged cook and a mother with a vivid imagination take the apple and warn the hoverboarding child away from the inferno before he careens head first into it. He whisks away as I place the apple on a corner of the grate and preside. After a few minutes, I use my husband’s welding gloves to wield the tongs so I can turn the skewers without scorching my fingers. As I do, I wonder what the bachelor would think. Would he, untethered by the chaos of a busy household think it a bit chaotic? He did seem awfully intent on being the host with the most. Not something I am doing as I pull the kabobs from the fire just minutes later and throw them quickly onto a platter for a not-at-all Instagram worthy shot. I toss a quick salad together and holler around the house until everyone arrives back in the kitchen.

In separate areas, I dish up the venison and salad to the humans while my son dishes up the biscuits to the dogs. We all, thankfully, eat.

And despite me scorching the hell out of the smallest pieces, the venison is really nice. Roasting it over the coals imparts a gloriously smokey flavor and lands some delicious char into the mix. The bacon is delightfully sweet coupled with the smoke. We have no problem whatsoever mawing these down alongside the roasted apple and a salad dotted with cheddar cheese. It tastes like quintessential New England. I chew and mull and think the only thing I might do differently the second time around is place the pepper and onion in large chunks along the kabob so I don’t lose the little pieces of them in the pit.

With my stomach full of genuine fuel, I head to the archives to see if I can track the bachelor, A. Lyman Phillips. Does the “A” stand for Allan or Albert or Andrew? Is it Alfred or Alexander or Anthony? I start with Google in case there is a very obvious answer, but I mostly come up with sales of the title across a variety of rare book platforms. The lowest price the first edition is going for is $650. Is this guy famous? I then head to Ancestry and throw a few searches in, narrowing to the turn of the 20th century to see if I might get lucky. No dice. As I pivot to newspaper archives I find much better results. The tip of my nose tingles like mad as I dive from one paper to another in pursuit of the delicious answer.

“A” doesn’t stand for Alexander or Austin or Anthony. No, not at all. A stands for…Amy.

This bachelor was a lady. Here’s her story.

Amy Lyman Phillips

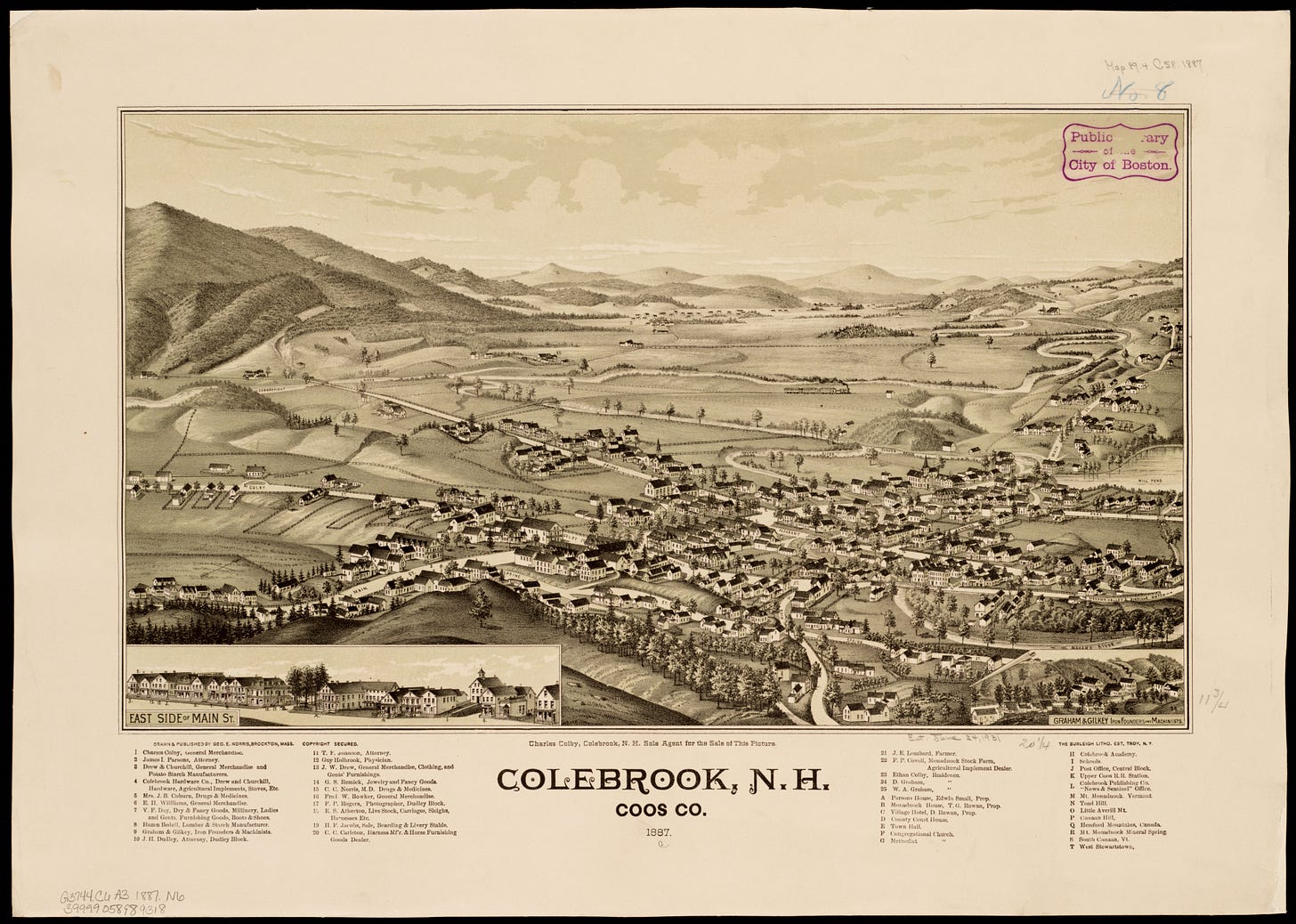

Amy Lyman Phillips was born in Colebrook, New Hampshire on April 1st, 1876 to Ida Lyman and William Phillips. I’ve been up that way. It’s UP that way. I think I got lost around there once when I was on my way to Stewartstown, which was just a stone’s throw away from Canada. Think Great North Woods. Think Upper Coos. The town has long been admired for its rolling wilderness, defined by its mountain views and waterways. The positions of those waterways and the abundant natural resources grew an economy. This wonderful urban view drawn by George Norris shows us a glimpse of the town as it was in 1887 (when Amy was about 11 years old). At that time, Colebrook was a busy little place producing lumber, shoes and boots, hardware, carriages, and, unique to their area, potato starch.

By the turn of the 20th century, the town also had lot of destination appeal. It featured transportation, inns, and local entertainment. By the advent of the auto, intrepid tourists were coming from all directions. Positioned as it was, Colebrook has been a scenic destination for travelers coming from Canada, Maine, Vermont and, of course, Southern points of New Hampshire ever since.

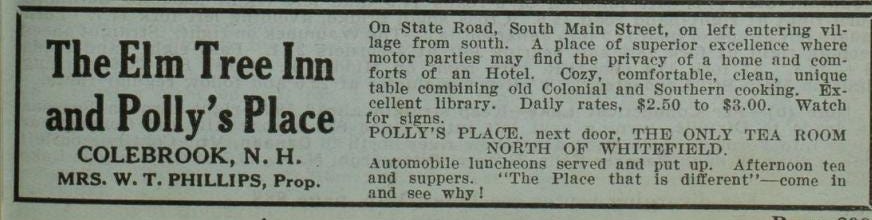

Amy’s family actually catered to those tourists. Granted, Amy’s father, William, was a carriage and sign painter. Amy’s grandfather was an inn proprietor. Ida Phillips, Amy’s mom, went into this line of hospitality work as well. She was a chef and proprietor, owning the Elm Tree Inn and Polly’s Place (which were eventually operated by Amy, herself).

Amy likely grew up alongside her mother, seeing guests come and go. She became aware of society, food, etiquette and more. But there was another element to Amy. She was a writer. And a good one at that. By the time she was grown, she had a discerning taste and knew how to communicate it. She was also a vibrant personality without too much of a shy streak — a great combo for reporting.

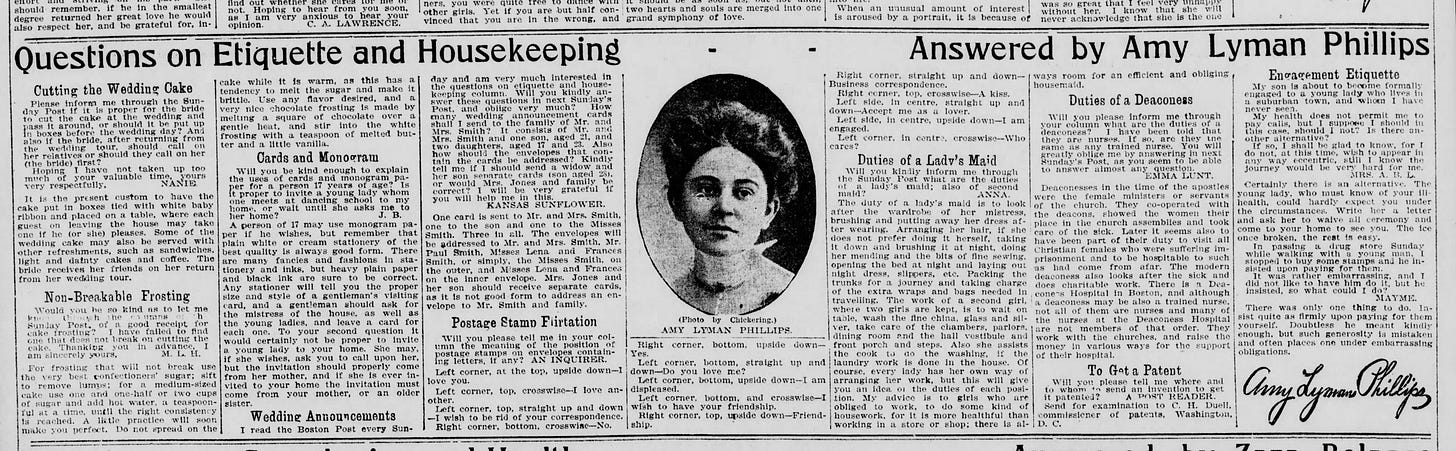

In the early 1900s, she wrote a popular column for the Boston Post called Questions on Etiquette and Housekeeping. There, she dished up the best suggestions for non breakable frosting, whether ladies should smoke, how to acquire a patent, and so much more. She lived in St. Botolph’s Studios around that time alongside a variety of other artists, writers, and scholars.

In 1904, she was managing editor for the White Mountain Echo, a newspaper particularly written for tourists to the White Mountain region of New Hampshire. They were a reliable local news source telling out-of-towners where to go, what to see which mountain to climb, and of course, which hotel to stay at and, most importantly, who might be there.

While splitting her time between Boston and the North Country, she was dreaming up A Bachelor’s Cupboard. It was written as a collection of fantastic recipes and suggestions for the single man and was fondly dedicated to “the sole survivor of the five bachelor’s of the shack.” I wish I knew who that was. As you know she wrote it under the pen name A. Lyman Phillips. In all other publications, she was referred to as Amy Lyman Phillips, so it wasn’t a huge departure or top secret name. It appeared to be generally well received, although, the New York Times stoked the fire a little in their overview of forthcoming Boston titles in August of 1906

Even though most publications referenced Amy’s pen name in conjunction with the title, others stated clearly it was written by a woman. In fact, in 1907, The Berkshire Eagle reported on the book and said “the average bachelor turns with a sigh of relief to the pages of a manual like “A Bachelor’s Cupboard,” written by A. Lyman Phillips, who, by the way, is not a man. Miss Phillips shows a keen insight into the foibles of the male creature…”

If there were a lot of grumblings about the bachelor’s manual being written by a woman, not many such articles landed in print. It seemed to be, generally, well-received and well circulated. I’m not sure how many printings it received, but the average price for the book is so high, today, it makes one wonder if it had a fairly small print run. Either way, it’s a beautiful book and Amy’s writing continued to take off from there. She landed pieces in Good Housekeeping, Vogue and Field and Stream.

Most of her works were articles, but she occasionally wrote essays and short stories. In 1909, at the age of just 33, she penned an essay entitled On Being An Old Maid which was published in The Smart Set: A Magazine of Cleverness. There, Amy expounded on the circumstances of “spinsterhood” and explained the many romances and heartbreaks that led to such an existence. There was West and Teddy and Harry and three different Franks. She explained that spinsterhood arrives like an auto going through a dark tunnel. One minute you’re young and fair and then you’re plunged into blackness, then out again with hopes renewed, then back into the dark once more. She said,

Philosophically speaking, being an old maid isn’t so bad— when one has a delightful home and doting parents…..But for the self-supporting woman who lives in her trunk in a hotel or a hall bedroom, politely speaking, it is Hades. I’ll wager that not more than one in a million doesn’t pine for a home of her own and a release from the bête noire of the weekly room rent and meal ticket. Poor things- they don’t even dare stop working to be ill. Have they a headache or a pain? They must work just the same — and with a cheerful face, or run the risk of being docked a day’s pay if they sit home nursing their woes.

This essay gives a glimpse into a somewhat fraught relationship with the single life. A desire for what might be found “on the other side of the fence.” We can see this same analysis in her romantic short stories, A Garden of Dreams and Two in a Tree which were published in 1910 and 1911 in the New York Tribune. And yet, Amy’s story would have been quite different if she had been married. In fact, around this same time Amy was editor of a popular food magazine and she traveled around the world looking for unique recipes. She was rubbing elbows with some very well-to-do people in Italy, France, Egypt, and beyond. During these times, she always wrote back to her hometown paper, The Colebrook Sentinel. She would pen letters on missing home while detailing trips to Gibralter or describing the contrast of the natural beauty of the North Country to the artificial beauty of Paris. She then would careen back to the U.S., her local paper diligently reporting that she was landing in New York or Boston and would be summering at Bretton Woods or the Mountain View House in Whitefield. She never stayed still.

In 1910, she was engaged as press reporter for Blanche Stuart Scott. If you’re not familiar with the name - admittedly she was new to me as well - she was the first woman to drive an automobile across the continent. On the side of her custom Lady Overland was written The Car, The Girl, and the Wide Wide World. Later, she was one of the first U.S. women to take to the skies.

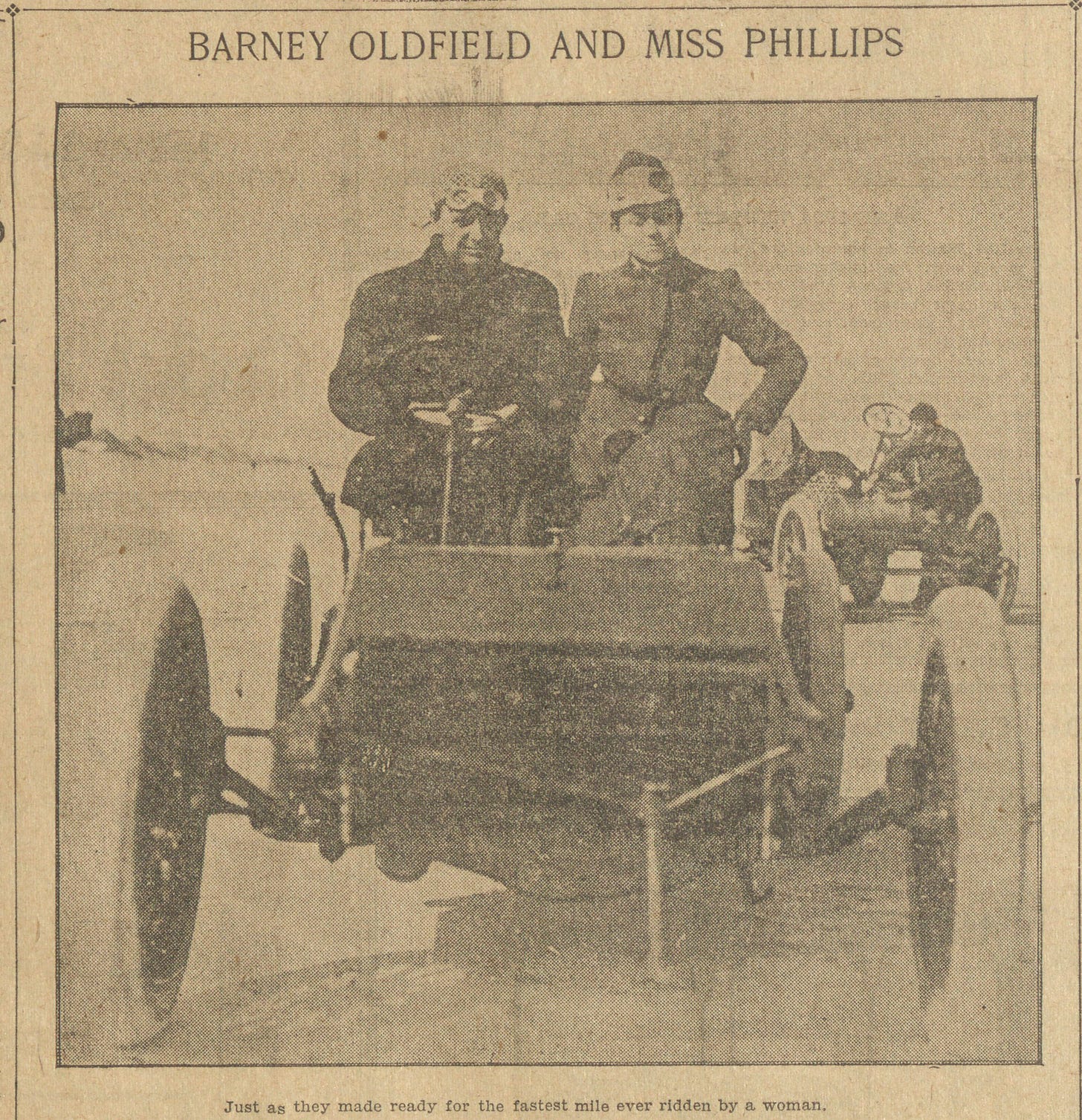

Blanche had one passenger. And that woman was our - always on the move -Amy Lyman Phillips. Amy was not new to the world of cars. In fact, she’d already garnered a “first” in automobiles. The Boston Journal of March 13th, 1904 ran this headline:

Barney Oldfield was a pioneer in auto racing. And Amy had noticed the cars speeding up and down Ormond Beach during one of her many seasonal trips to Florida. Being a precocious person, she said she was interested in taking a ride and Barney agreed. For the event, she wore a raincoat, a cap, and a unwieldy pair of goggles. Proper racing attire.

As they took off, she was told “grip tight, bend your head low, and keep your mouth shut.” Amy was delighted by the ride and told the reporter she never did have too much trouble with her nerves and the trip didn’t change that. In fact, she said, “it spoiled me for ordinary touring in motors, this ride.”

Well, needless to say, going on the first cross-continental journey chauffeured by a woman was not an ordinary tour. Especially not with a character like Blanche Stuart Scott. I mean, look at this picture.

Miss Scott and Miss Phillips started out on a seasonable May day. Their goal was to travel across the U.S. without any masculine aid. Miss Scott knew how to do some auto maintenance and they only planned to seek help in case of an outstanding emergency. Amy reported back to the press along the way. They drove up mountains, along beaches, through abandoned mining towns and got lost in the Nevada desert for a whole day when the speedometer went wonky. All along the way, they visited friends and met fans. On Saturday, July 23rd at 10am, Blanche drove her car onto the ferry for San Francisco and was greeted on the other side by a large throng of people. They made it. She said

We have enjoyed every inch of our long trip and have succeeded in proving to the world that the trip across the continent can be made by women as well as men. We had but little trouble with the car although we experienced some little difficulty in making a few of the long grades in the steep Sierras.

“Overland Bulletin,” Appeal-Democrat (Marysville, California) 25 July 1910, p. 7, c. 2 and 3; digital images, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 10 January 2025)

By the close of 1910, Amy had traveled all around Europe and beyond and road-tripped across the U.S. Yet, she seemed to have two favorite places. One was, of course, her home, Colebrook, New Hampshire. The other was sunny West Palm Beach, Florida. She lived between these two places, seasonally, for the rest of her life. In West Palm Beach, she became a popular resort reporter. Her columns kept people up on the social happenings and influenced trends. There, she’s also well remembered as founder of the Peggy Adams Animal Rescue League. In 1924, a group of women got together on her porch. They were concerned about the dogs that were abandoned at the end of each winter season. They got their start creating makeshift cages at the abandoned TB hospital. The league is still in operation, though in a different location, today.

She also learned to fly in Florida. In 1918, when Amy was in her 40s, The New Hampshire Farmer and Weekly Union reported that Amy was learning aviation. Reportedly, she went up 3200 feet in the air - flew almost to Ormond - and up and down the peninsula several times.

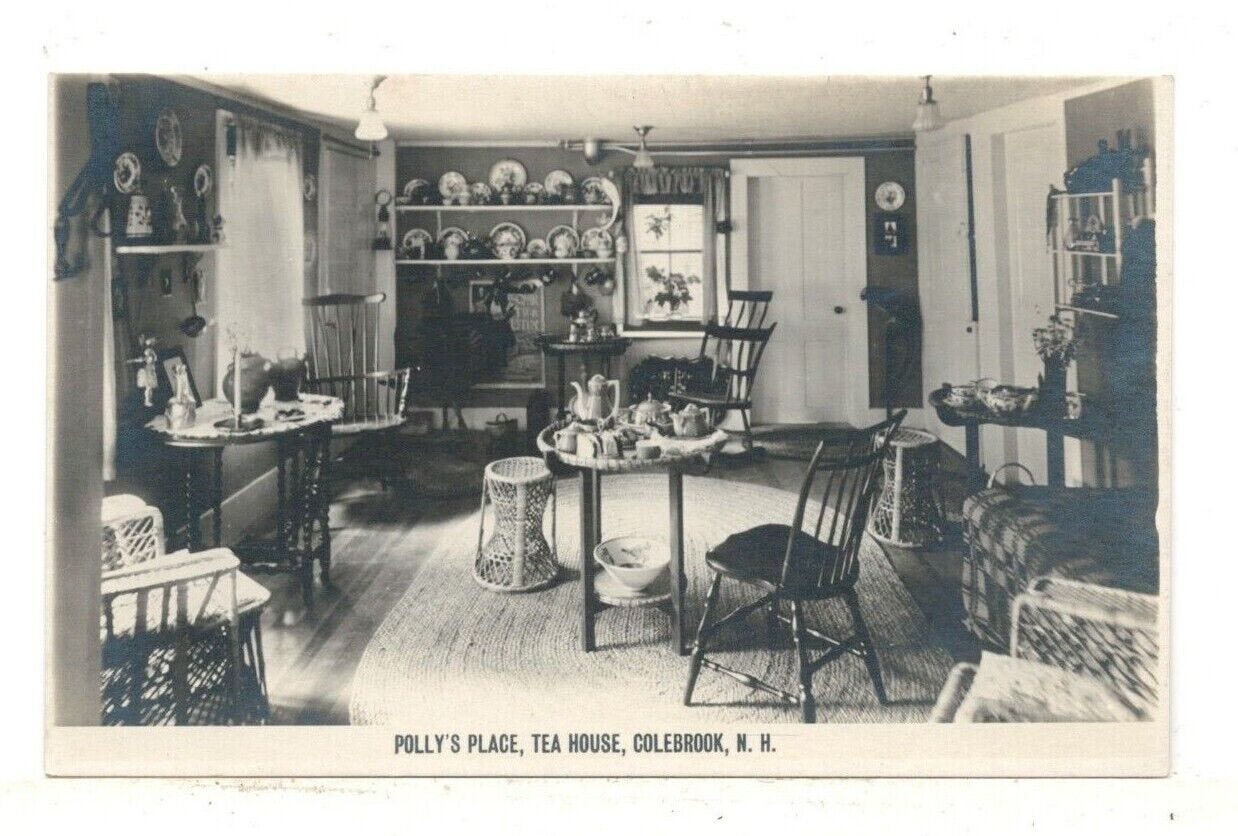

Amy summered in Colebrook where she was born. She was a close confidant and correspondent for many White Mountain hotels. But she was also proprietor of the Elm Tree Inn and Polly’s Place Tea Room. By 1923, both of her parents had passed away, but she retained the properties. Below, we can see a lovely image of Polly’s Place from the outside, doors flung open, ready to welcome visitors. The sign reads Polly’s Inn, Rooms & Private Baths, Service A La Carte, Amy Lyman Phillips, Proprietor. Is that her leaning on the bench by the window? It seems likely.

Polly’s Place was renowned and visitors came from everywhere. It was lauded as the only tea room between the White Mountains and Dixville Notch and it had a dining room furnished with pottery from Italy, Brittany, Holland, Hungary, Spain and Belgium. What a collection. From Amy’s travels, no doubt.

Amy didn’t seem to slow down as she aged. By then, the travel was deep in her bones built on 4+ decades of going from here to there and back again. 4+ decades of being a bachelor. Even after injury, she tended to get up and go when she felt like it, as was evidenced in 1958 when she fled the Stewartstown Hospital after a 5 months stay for a broken hip. Her sister, Gertrude, had passed away and she got up and left to attend to the funeral arrangements in Florida. Four years later, Amy died there. As she did in life, so she did in death: she traveled home once more. She was buried in Colebrook Village Cemetery in 1962.

Here, the fire has long since burned to coals and I’m afraid I’m not really ready to part with A Bachelor’s Cupboard or Amy’s story just yet. I find myself continuing to peruse the pages, discovering something new upon each visit. In her chapter On Being a Bachelor she says:

The old Greek maxim, “know thyself,” and that other, “ To thine own self be true,” build a creed of greater worth than tomes of ancient lore. “The hand clasp firm of those who dare and do — halfway meets that of those who bravely do and dare.”

That sure sounds like Amy, doesn’t it? She traveled the world, jumped in cars and planes, ascended and descended mountains. She wrote and ate and drank and flew. Maybe she was born self sufficient. Maybe, she grew into it by necessity. Then again, maybe that’s just how they’re made in the North Country, springing from the trees, a touch larger than life. Either way, she sure was a person who would “do and dare.” May we all take a page from her playbook. That playbook is A Bachelor’s Cupboard, and it just happens to be written by a lady. Her name was Amy Lyman Phillips.

Thank you for reading Soulspun Kitchen, where we explore recipes from the grave. It was an absolute blast to learn about Amy Lyman Phillips. Special thanks go out to repositories who kindly helped with this research, including the Colebrook, New Hampshire Historical Society and the Colebrook, New Hampshire Public Library. Thanks also to repositories who make fantastic resources available online, especially useful in this case was the Boston Public Library’s Leventhal Collection, as well as Bethlehem Public Library’s collection of the White Mountain Echo, as well as Ohio Memory’s historical photograph collection. Any and all historical mistakes or misinterpretations are wholly my own. If you liked this article, please like, share, and subscribe.

This has been updated with a better scan of the Boston Sunday Journal Article featuring Barney Oldfield and Amy Lyman Phillips. Thank you to the Boston Public Library for the quality scan.

Your paid monthly subscription helps me buy death and birth certificates, pay research expenses, and purchase ingredients. Thanks for being here and I hope you come again for more recipes from the grave.

Great find! A whole new (or old) spin on the bachelor life. Bravo 👏

What a delightful discovery, this Amy! And so sublimely written! Thanks for bringing her memory back to life for us, Er!