It’s January of 2025 as I write this. Los Angeles is burning. America, likewise, is on fire. The news feed sends me into a tailspin — and everyone’s reaction to the news feed sends me further spiraling. That’s how I find myself in my office. That’s how I find myself at the bookshelf, thumbing an old cookbook. Perhaps there’s something good here. Something good to eat and someone good to research. An opportunity for inquiry and archives. A firm step away from the present. That’s how I find myself, once again, flipping the pages of the Federation Cook Book.

This book of recipes was compiled by Mrs. Bertha L. Turner around 1912. It’s a collection of tested recipes contributed by the Black women of the state of California. I was first introduced to this book by the modern day cookbooks that embrace historical recipes written by Toni Tipton-Martin (Jubilee and Juke Joints, Jazz Clubs and Juice). I’ve glanced at The Federation Cook Book more than a time or two since, wondering what academic might pick it up and make some sort of dissertation on how this group of Black women changed Los Angeles. They were working hard building social programs, fighting for voting rights, and creating inclusive communities. I know this because every time I pick a name out of this book and take that name to archives, I run into another woman with her head square on her shoulders, usually running from the Jim Crow South to the hills of California. Obviously, she was looking for something different.

I’m not sure if she found it or if she built it.

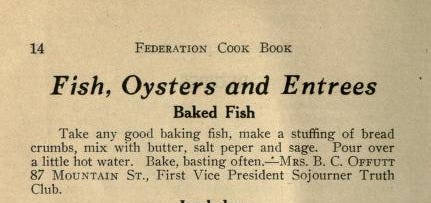

When I open the book, this time, I land on the name of Mrs. B.C. Offutt. The recipe is short and sweet. She simply states:

Take any good baking fish, make a stuffing of bread crumbs, mix with butter, salt peper and sage. Pour over a little hot water. Bake, basting often. —Mrs. B.C. Offutt, 87 Mountain St., First Vice President Sojourner Truth Club

One thing I’m not is a natural in the kitchen. One thing I am is an over-thinker. So, as I read this spare recipe I’m left with questions. Mrs. Offutt doesn’t say exactly how to stuff the fish, for one. So how exactly am I stuffing the fish? Do I grab a trout and stuff it like a thanksgiving turkey? Do I cake the breadcrumbs and start rolling?

One Saturday afternoon, I’m hanging with a friend while our children scream downstairs. We’ve taken refuge in an upstairs bedroom, a box of artifacts from Jewish New Jersey, 1910, are sprawled across the rug between us. I bring up the fish stuffing conundrum.

“I think it’s like a topping,” my friend says confidently. We debate the possibilities until it’s decided. It’s to be piled on top, like a zucchini boat.

I go home and pull items from the freezer. I know I have fish in here somewhere. Squid. Nope. Scallops. Hard pass. Ah. Bluefish. Is bluefish a good baking fish? Um. No idea, but it’s available and needs to be eaten, so that’s what it’s going to be. “Now’s your moment,” I think, as I get to work.

I grab some sourdough that’s been sitting on the counter for a day and cut off four big slices. I place them in the oven at 250. While the bread dries my son and I watch a documentary on skinwalkers.

Once the bread is dried and cooled, I blitz it in the Cuisinart until I have some nice rustic crumbs. Mrs. Offutt gives no real quantities or instructions, so I do my best to create a stuffing with the ingredients she suggests. I place three tablespoons of butter into a pan and melt them. I mince 7 sage leaves and drop them in the hot butter, then I throw in two cups of my homemade crumbs. I start adding salt and pepper to taste. It takes about 2 solid pinches of salt and several grinds of pepper until it’s up to snuff.

My husband walks into the kitchen with doubts. “Bluefish, huh. You know bluefish is a tough fish, right? It’s not the best fish?”

“Well, it’s probably best loaded with breadcrumbs, then, isn’t it?”

We agree and he heads back out of the kitchen.

I place stuffing on each fillet, and use toothpicks - ok, that’s a lie. I look for toothpicks and can’t find any, so I snap skewers into pieces to secure the fillets in a boat-like position. By the time I’ve filled my three fillets, I have a little extra stuffing, so I tuck the rest around the fish and then pour on a little bit of hot water.

I slide it into a 400 degree oven. After ten minutes I take a look. It’s pretty well done, but pale, so I crank it to broil and let it work for 3 minutes until there is a nice golden crust.

It smells good. It looks good. I plate it up, serving it with some garlicky bok-choy and a little rice pilaf. While I fumble with my camera, my 10 year old son informs me that my plate looks so bad it makes Nick DiGiovanni sad. So, he re-plates it for me and, to be honest, it does look much better.

As I take my first tentative bite, I realize I’m not really prepared to enjoy it. With the suffocating reputation of the bluefish now front of mind, I’m wondering how “meh” it will be - and how long it will take to force down. But honestly, it’s delicious. The stuffing is buttery and warm. It’s very reminiscent of thanksgiving stuffing because I didn’t joke around with the butter and salt. The pepper paired with the sourdough gives it the tiniest little sting. Some of the stuffing is soft while other pieces crunch - and the fish flakes apart perfectly. Everyone finishes their plates. Maybe we’re carb-forward, maybe we’re just not picky eaters. Maybe Mrs. Offutt had great taste. Either way, this one is such a win to me.

I go to bed still surprised - and nourished - and alive with questions about Mrs. Offutt and her dish. For instance, on what occasions did she plate this up? Who did she plate it up for? Was it a family favorite? Was it a borrowed or original recipe? I never did find any of those things out, but after a deep dive into the archives, I can tell you a thing or two about Mrs. Offutt.

Georgia Elizabeth Abbington Kenner Offutt

Mrs. B.C. Offutt was born Georgia Elizabeth Abbington in Missouri on August 21st, 1868. She was born Black on the heels of the Civil War. Her parents may have been George and Ellen Abbington.1 She attended Lincoln University in Jefferson City for a short period of time in 1889. Lincoln was established by two Civil War regiments of emancipated Black soldiers. Their vision was to start a school for other free Blacks, which would focus on study and labor. It opened its doors on September 17th, 1866 with two students attending. By the time Georgia was there, over two decades later, enrollment had expanded exponentially and it had started to offer college level work. Georgia didn’t stay for long at Lincoln. It might have been funds. It might have been love. We don’t know for sure. Nevertheless, she married a blacksmith named Rodham F. Kenner in St. Louis in October of 1891.

Georgia and Rodham, often called Rod or Roy, moved from Missouri to Los Angeles shortly thereafter and were quick to start a family. Bouncing through Georgia’s timeline, I noticed that Roy died young, and I pursued his death register only to run into a cause of death that I’d never seen before.

It looked like this:

If I’m not mistaken, that says “knife wound inflicted by Carazz—”

Huh.

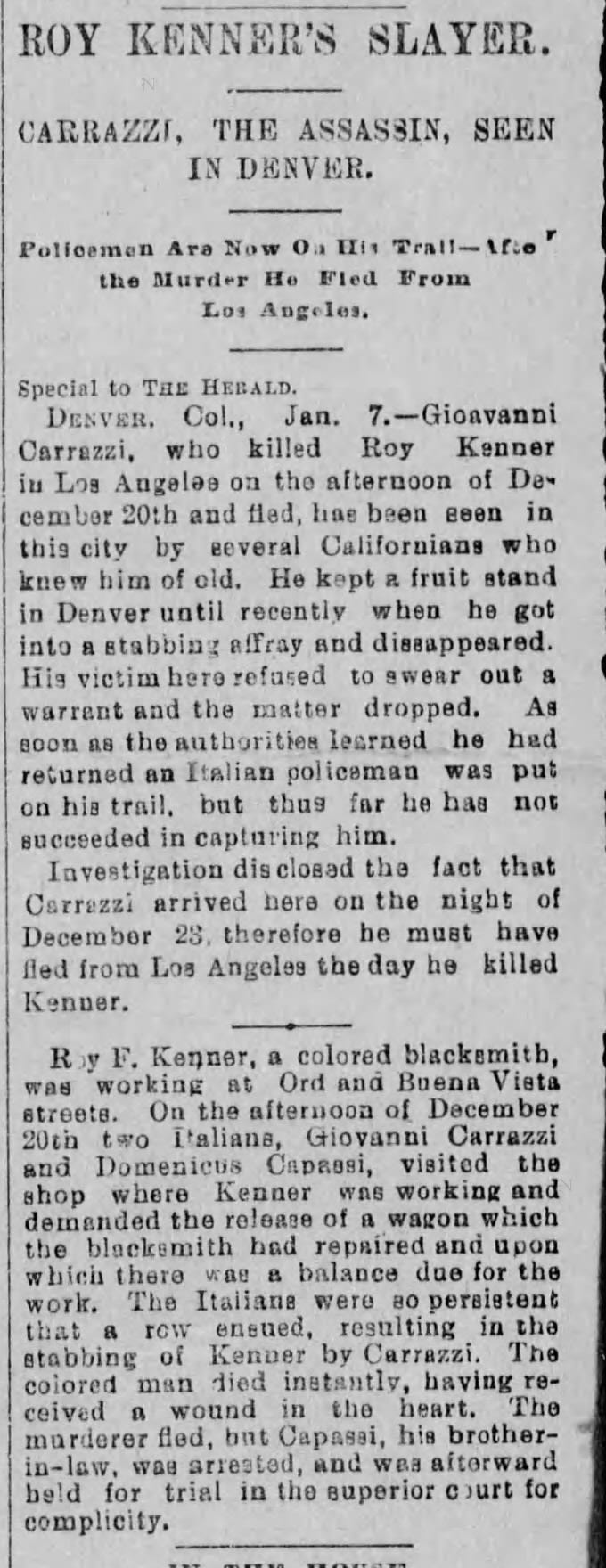

I jumped into the newspaper archives and soon found evidence to back up the note from the attending physician. For the next hour I was down the archive rabbit hole replaying the horrible day.

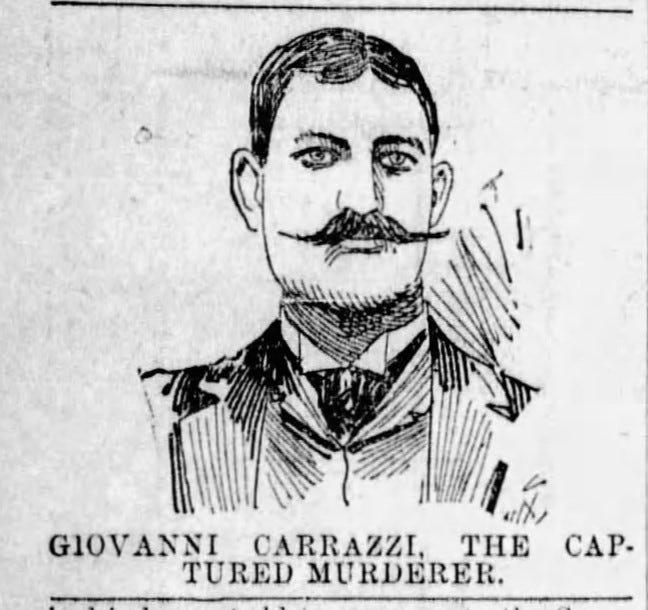

Roy was working in the Buena Vista Street blacksmith shop on the 20th of December, 1894. He was doing some repairs when a man named Giovanni Carrazzi came in demanding his wagon. Naturally, Roy suggested he would have the wagon once he paid for the repairs. Giovanni refused to pay. Roy returned to his work and Giovanni stabbed him in the back, right through the heart. Roy was rushed home while Giovanni fled the scene. Unfortunately, nothing could be done to save Roy.

In the meantime, Georgia (and their one year old son, Byron) waited with baited breath while the authorities tried to locate the murderer. Giovanni had not only left town, but soon fled the state. The authorities circulated the news far and wide. He was seen in multiple states before being caught in New Jersey.

Carrazzi’s get-away was foiled by his own wife. They had foolishly thought they were in the clear and corresponded in order to meet up. The police shadowed his wife to his hiding place. There, they were able to make the arrest and extradite him back to Los Angeles to stand trial.

Sadly, Giovanni Carrazzi was only given 10 years in prison for the murder of Roy Kenner.

Georgia had no choice but to move on. She was, after all, still here. She never seemed to let Roy go, though. I only say this because from that time period forward you see her middle initial changes from “E” for Elizabeth to “K” for Kenner. It’s a small symbol found across records, entries, and documents, but it’s there, like she was keeping a piece of him close.

Georgia remarried in 1897, this time to Boone Offutt. Boone had a variety of different jobs over the years from floor finishing to cabinetry to railway work. Later, he worked for the county court house and Bank of America. They had a daughter named Ruby in 1900. Georgia raised Ruby and Byron over the next two decades, and during that time she didn’t have a strong career focus, but was extremely active in her family and community, especially with her participation in clubs. By the time Ruby was 12 and Byron was 19, Georgia was vice president of the Sojourner Truth Club.

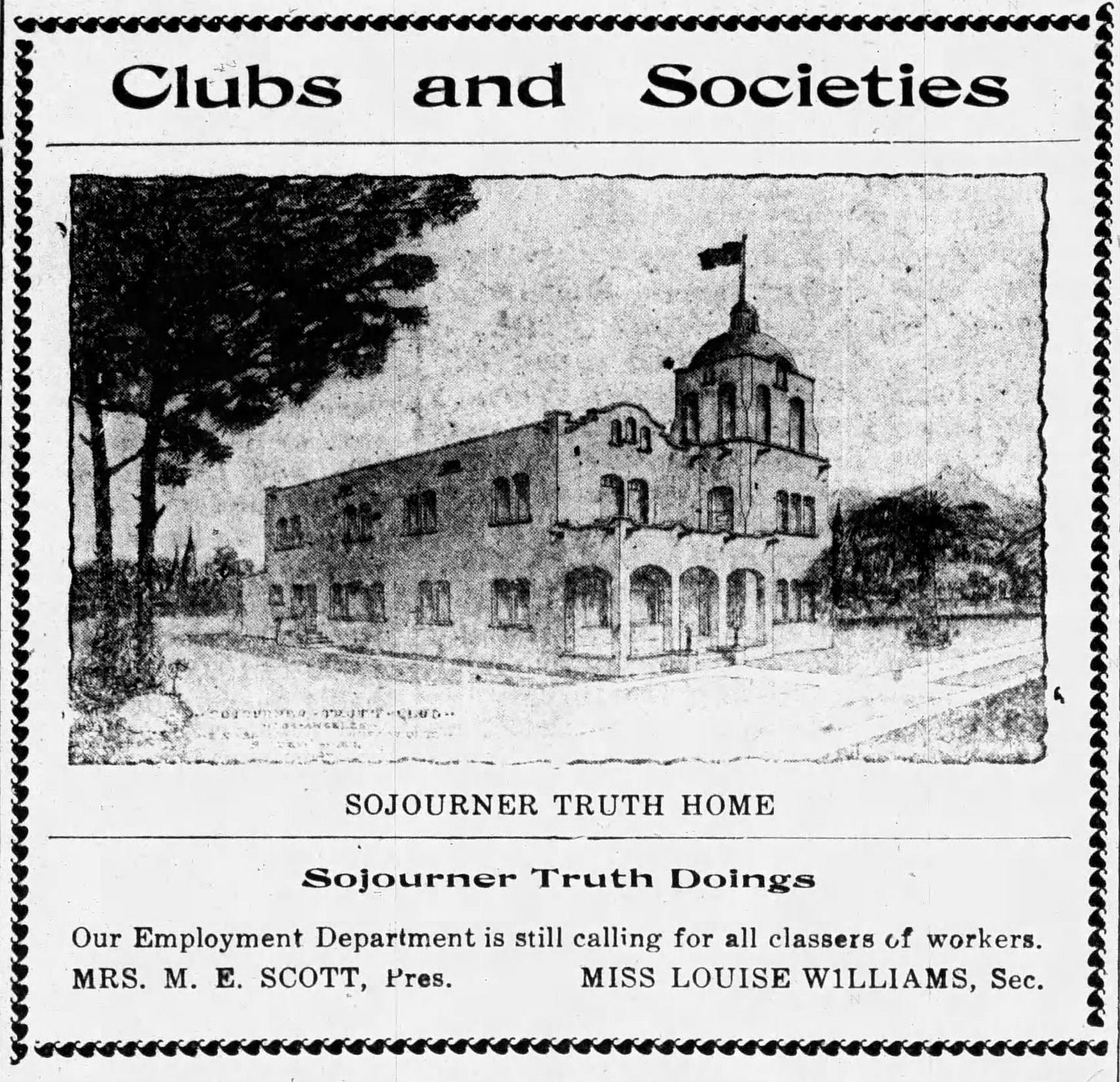

The Sojourner Truth Club, named after abolitionist and women’s rights advocate, Sojourner Truth, had a strong focus on bettering the conditions of working girls. The L.A. contingent dreamed of creating The Sojourner Truth Home; a safe place for working Black girls with unstable home situations. During Georgia’s era, the club began to discuss this home and brought it to fruition. She was likely heavily involved with the inception of the institution. In 1906, they had some funds in the treasury and were able to supply temporary housing while the institution was dreamed up and constructed. By May 1913, the home was opened and dedicated.

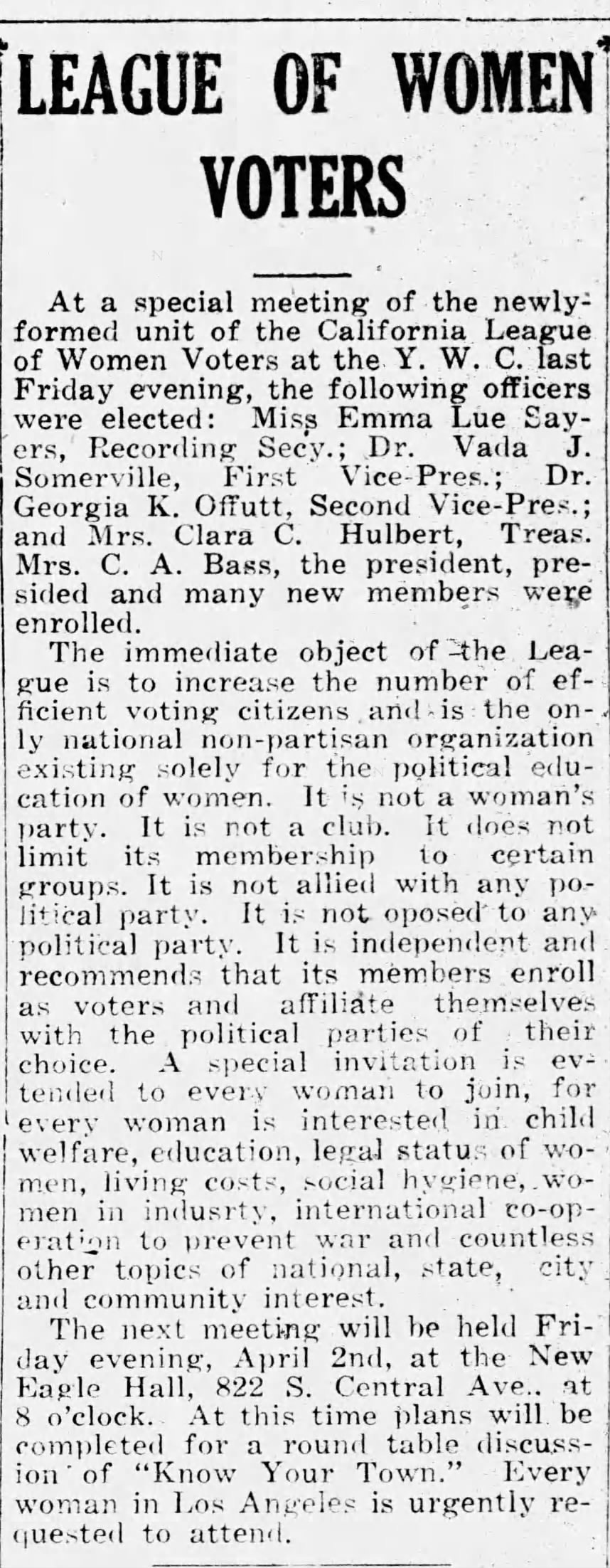

Georgia is also remembered as a suffragist. California women advocated for - and won - the right to vote in 1911, making them the sixth state in the U.S. to do so. On the 1914 voter roll Georgia was affiliated with the progressive party. Over the years, she declared herself democrat, republican, progressive and sometimes “declined to say.” In 1926, she took on the role of vice president of the newly formed Los Angeles unit of the California League of Women Voters and was extremely active in getting California’s women to the polls. This newspaper clipping from the 1926 California Eagle introduces the group.

The immediate object of the League is to increase the number of efficient voting citizens and is the only national non-partisan organization existing solely for the political education of women. It is not a woman’s party. It is not a club. It does not limit its membership to certain groups. It is not allied with any political party. It is independent and recommends that its members enroll as voters and affiliate themselves with the political parties of their choice.

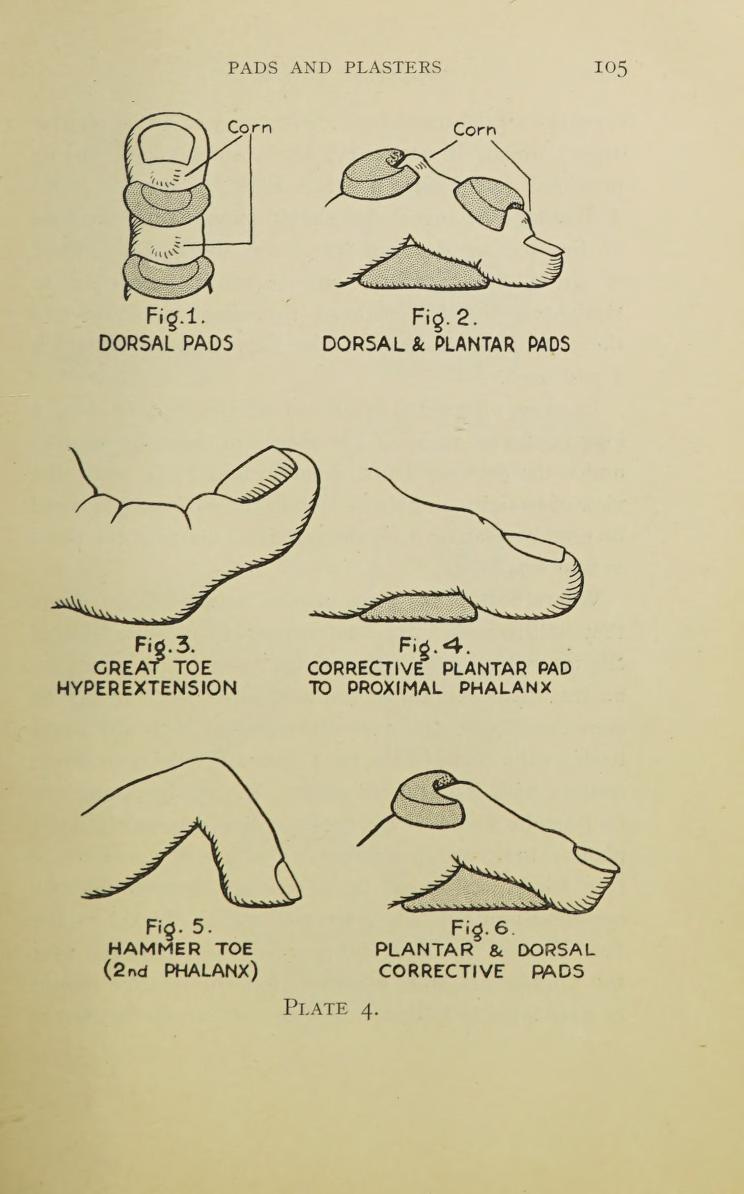

As her children aged into adulthood, Georgia pursued higher education. She attended the San Francisco College of Chiropody where she earned the degree of Doctor of Orthopedic and Surgical Chiropody in 1922. Chiropody is the treatment of feet and their ailments. Think this:

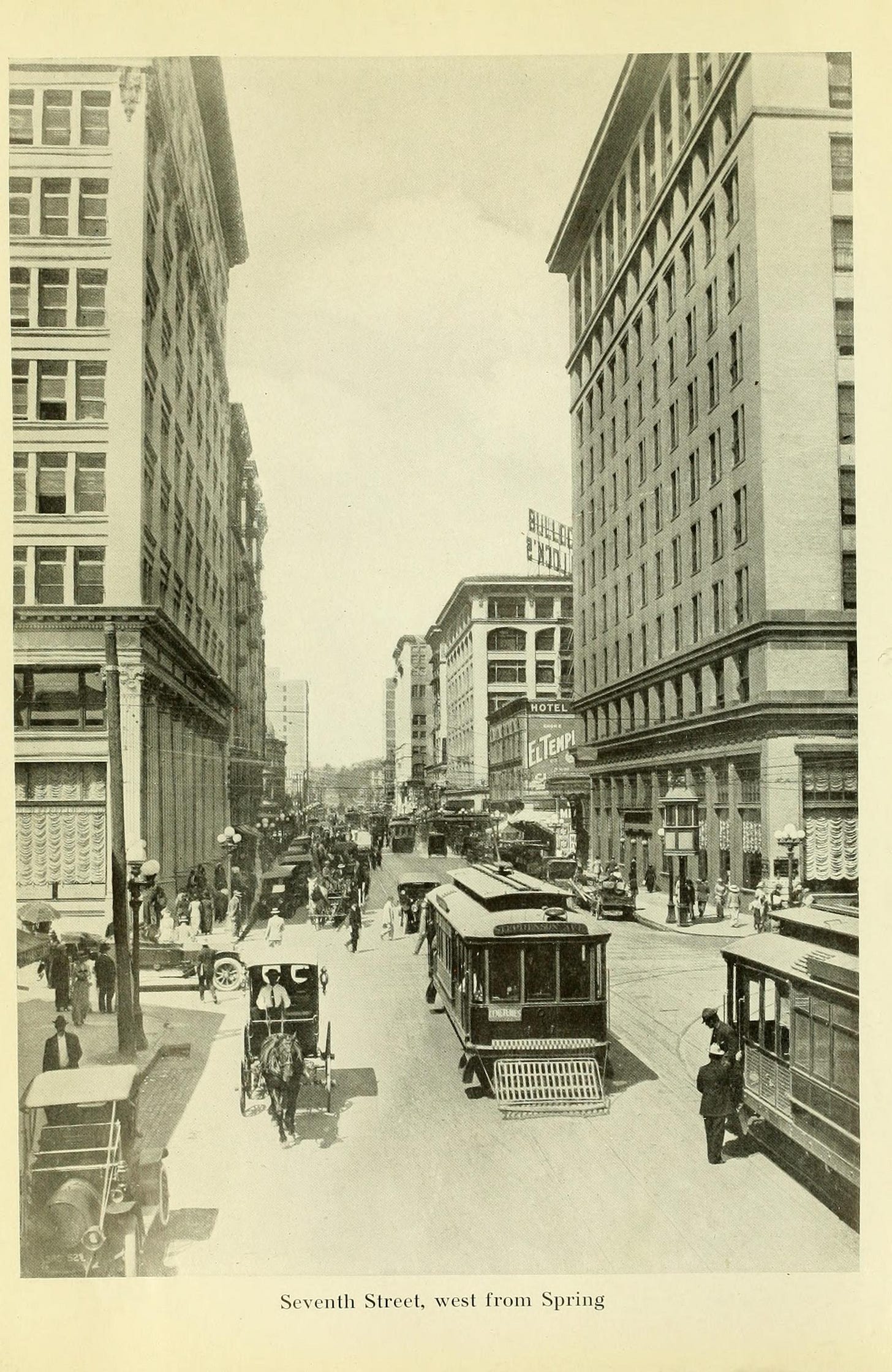

Georgia practiced Chiropody from her office on West 7th Street for decades. I love this 1914 shot of 7th Street, full of pedestrians, trolleys, autos, and horse and buggies. Georgia would have known L.A. Streets like this, and seen the transformation when buggies were fully eclipsed by cars.

Also in the 1920s, Georgia was a member of the Lincoln University Alumni Association and the Rho Psi Phi Medical Sorority.

Rho Psi Phi was founded in 1922 by Mary Jane Watkins Edwards. Emily Brown Childress established the California Rho Psi Phi sorority. Their focus was on charity, study, sisterhood, and progress in the medical field. Georgia, an integral part of this group, acted as treasurer, and is credited for being outspoken in the medical field about the lack of adequate medical care for Black women. Here’s an image of the sorority circa 1924. Do you think Georgia is in there somewhere, staring back at us? I think she might be.

Georgia was always out in the world, rubbing elbows with L.A. society and was well known for putting on a great party that infused fun and intellect. The California Eagle reports on many social occasions such as valentine’s day parties and luncheons. She was also a member of the Pacific Beach Club. The club was a beach resort for African Americans who were mostly barred from the area beaches crowded by whites. The club ran beauty and dance contests and allowed Blacks a sanctuary along the ocean. Unfortunately, as the full resort was being finished it met with a malicious and incendiary end.

The 1930s brought loss at home. Boone died suddenly in 1932 and then their daughter, Ruby, died in 1934 at the age of just 34. Ruby is remembered as being a product of the public schools and for carrying that legacy into teaching at the Holmes Avenue School for 14 years. She died after what the newspaper characterized as a short illness.

In her later years, Georgia continued her medical practice, working with patients all the way up until just a few months prior to her passing. She remained a club woman, taking part in the Delta Mother’s club in her older age. She passed away on the 7th of October, 1949 and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Los Angeles.

As I finish my research I realize I only know the story of this remarkable person because of a baked fish. Did you know her story before this? Her biography isn’t one I ran into in history class. Her steadfast local work toward equality in medicine and politics are there only if we take the time to look across databases and through the archival record. As a genealogist I sometimes find myself so interested in the nuance of a year, that I might let the general historical context fade away. But it doesn’t serve us to forget historical context, does it?

Georgia was born Black in the Jim Crow era. She worked, climbed, culled, and built the world around her during great personal loss, segregation, and suffrage. She saw the great depression and two world wars. She did not live to see Civil Rights or desegregation of her schools or beaches.

And yet, narrowing the lens can also be a beneficial research practice. When we scrape up the details of a life story, we see a person - and her personal pursuits. Georgia pursued education, reached out to sisters and affiliates, made political change, undertook charitable causes, and actively healed people. There was certainly pain and loss and racism and violence, but the record shows that Georgia steadily moved forward, toward what she loved, despite that.

I slide the Federation Cook Book back onto the shelf. Just until next time. As I stand fully in the present day, I’m enriched by history. Enriched by looking at a life well-lived. Reminded that perhaps the antidote to a mad world is simply the refusal to go mad with it. It’s the steadfast forward trod toward something better. Starting with what’s in our immediate vicinity.

Thank you for reading this biography. I really enjoyed studying Georgia Kenner Offutt. Many thanks go out to repositories and historical societies who were able to reach out despite the roaring fires. Especially thanks to the County of Los Angeles Record and Clerk’s office. Thank you to Lincoln University archivist, Mark Schleer for pulling school records. Thank you, also, to the Pasadena Museum of History for peering into your archives for the women of the Federation Cook Book whenever I come calling. To the Missouri County Clerk, I appreciate you taking the time to pull vitals and point me in the direction of other archives. Thanks also to those archivists digitizing materials on Calisphere, especially for the Miriam Matthews Photograph Collection at the UCLA Library Digital Collections.

Any mistakes, misinterpretations, or mischaracterizations made herein are wholly my own.

Discovering the parents of Georgia Abbington is harder than you might think. I was unable to find a birth register for Georgia. Her first marriage to Rodham Kenner is available, however, Missouri marriage licenses didn’t require parentage unless the person was under 18. Georgia’s death certificate was acquired but it marks mom and dad as unknown. A certificate for her second marriage in L.A., but likewise, does not include parental information. An interesting school record at Lincoln University showed that Georgia was enrolled by Ellen Abbington (Parent/Guardian). Georgia’s parents may have been George and Ellen Abbington from Missouri, but this theory requires more research.

This takes so much sleuthing! Thanks for doing & sharing.

(So many interesting details -- In order to catch Carrazzi, "an Italian policeman was put on his trail"...)

Erin: I enjoyed your story and particularly the part about bluefish. I grew up on Long Island and used to use a simple bamboo fishing pole to catch bluefish each spring when they'd run off Long Island song. I like the way you weave history and cuisine together!