It looks like there’s been a murder in the kitchen.

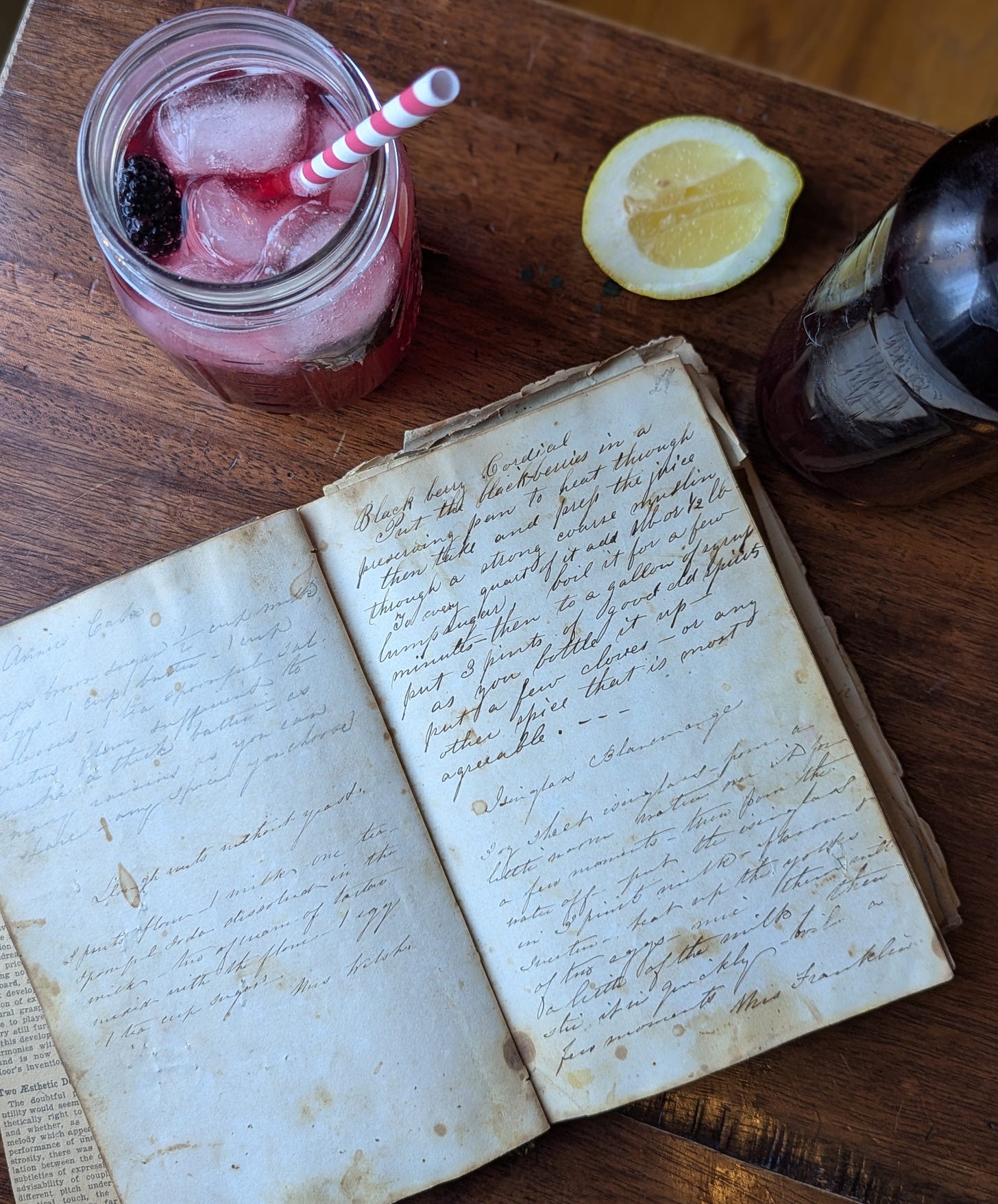

There hasn’t been a murder, of course. It’s just that Mrs. Dubois’ blackberry cordial (written in a firm hand somewhere between 1850-1879) has me in a bit of a twist. The antique book simply reads:

Blackberry Cordial

Put the blackberries in a preserving pan to heat through, then take and prep the juice through a strong coarse muslin. To every quart of it add 1 lb to 1/2 lb lump sugar. Boil it for a few minutes then to a gallon of syrup put 3 pints of good old spirits. As you bottle it up - put a few cloves - or any other spice that is most agreeable.

I’d started by giving the blackberries a bit of water. Then I gently heated them until the contents of the pan bled a dark blue/purple - and the steam smelled like jam. I even strained them pretty well. Things had gone wrong because some of the juice had remained in the pulp bowl, and in an effort not to waste I’d put the pulp back to a good coarse cloth, twisted it tight, and began to squeeze only to have it explode all over me, splat across the counter, and drop into the open utensil drawer.

Gross. I groan and start wiping up the berry mess-before it stains the countertops. What the hell am I doing, anyway?

If you know me, you know I’m a genealogical researcher, not a cook. Far from it. More like a certified kitchen troll. I’m much more comfortable tracking the dead than prepping a drink. The truth is, I’ve never made a cordial before. I’ve never even sipped a cordial. And, somehow, I got it in my head I should start with a mysterious recipe from over 170 years ago. And there are just 25 minutes left before I have to be in the pick-up line for school.

Digging the last of the berries from some serving spoons, I take a moment to reconsider. Maybe, like any research, there are parts of the process that are non-linear, messy, and potentially fraught. Maybe prepping cordial from 1850 is research?

OK, then. In that case…

I slide the pulp into the compost bin and look to the pot. From 8 pints of berries, I’ve only managed a quart and a half of juice. Nevertheless, I add 1.5 lb sugar to it and set it to a very gentle boil. Soon enough, a dip of a spoon delivers a dark sweet berry sip. With the kitchen in shambles and fingers stained a deep purple, I remove it from the heat and leave to get the kiddo.

Later on, as instructed, I put a good old spirit to it. Honestly, I add a bit more than Mrs. DuBois says. She had put only 3 pints of spirit to 1 gallon syrup. I don’t have a gallon and I’d read that 2 parts alcohol to 1 part syrup would be the appropriate cordial ratio, so I put 2 parts Grey Goose Vodka to 1 part simple syrup.

It leaves me with 4 cups of bright simple syrup to play around with! And plenty of spirited cordial to enjoy. I pour it into clean bottles and place them in the fridge, feeling just a little triumphant.

The next morning I head to the library where I work at the reference desk. My coworker and I start chatting about holiday preparations.

“I made a blackberry cordial from a recipe from 1850,” I say as I clip the obituaries for our index project.

“Sounds delightful as long as you don’t kill anyone with it.”

Huh. I drop the obits onto the desk.

OK. I hadn’t thought of that. What could go wrong with simple syrup and vodka? I hadn’t found a cordial from 1850. I’d made one with fresh ingredients. In my path of historical research, things usually go sideways with the addition of arsenic or strychnine. Especially strychnine. You know?

8 hours later, I’m back in the kitchen to make sure I won’t kill anyone with the cordial. Starting with myself.

Research.

Sip. smack smack.

Huh.

Sip Sip Sip.

It’s nice. Warming. Bursting with berry flavor. And best of all, I’m alive.

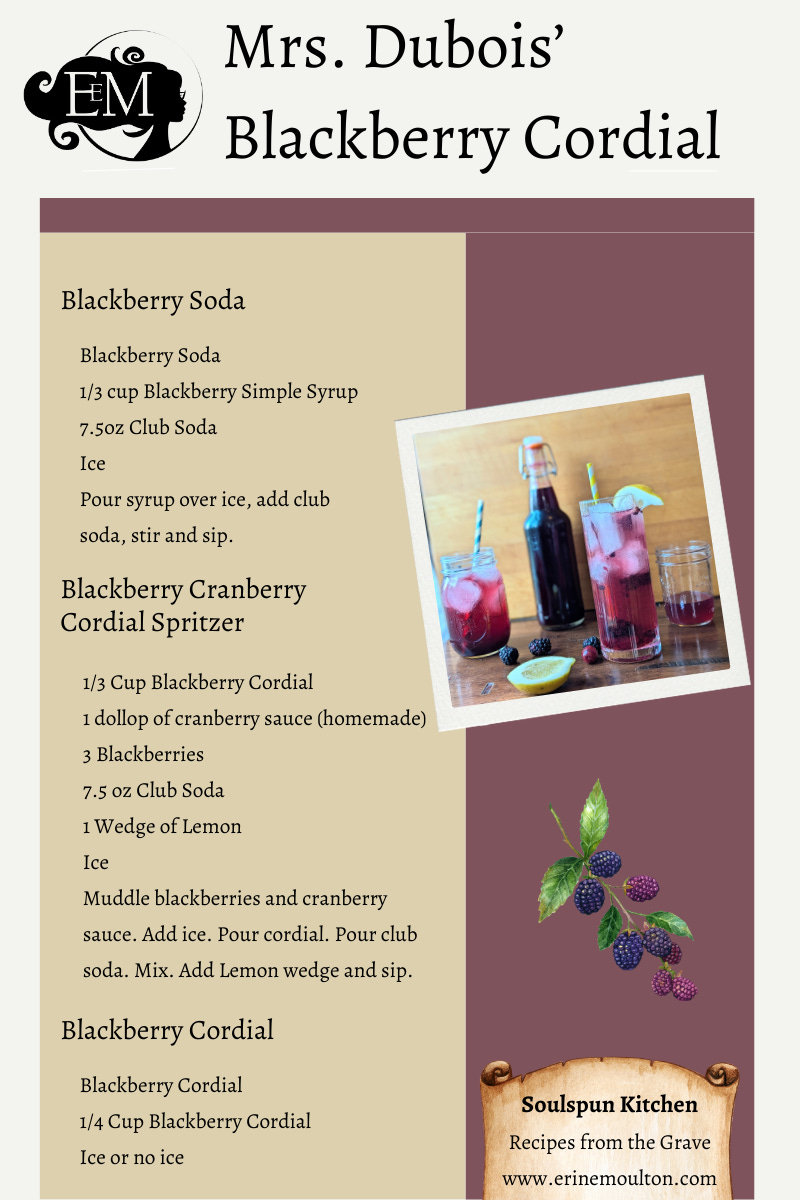

Between the simple syrup and the cordial, I have enough to make a few alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages for the festivities.

So I make these:

I imagine a mixologist would have strong feelings about ratios and flavors. If you are a mixologist with strong feelings and flavors, let’s chat about how to do this right. Mrs. Dubois gave no guidance. I’m grabbing things that are available in the kitchen. Plus, I’m drinking some random cordial from 1850, so let’s be honest, I’m playing around.

Frankly, I’m having fun.

And as I sip, I wonder about the woman who wrote the recipe down. How did she take her cordial? Who was this lady, anyway?

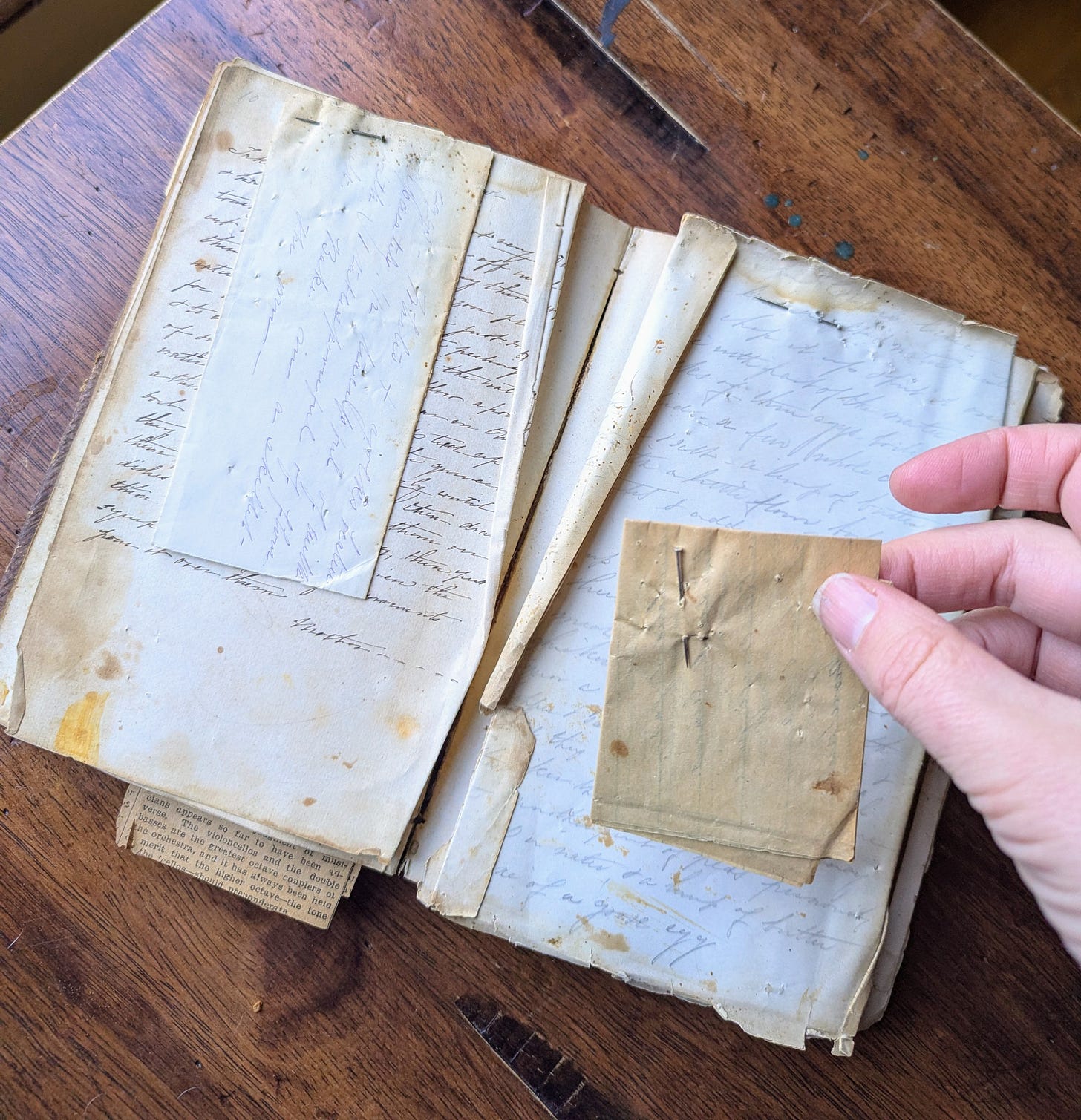

I’d come into possession of this tattered book by my dear friend, Ginger. She’d snagged it at a shop in Middlebury, Vermont and tucked it away for me.

Maria C. Dubois, Warren - Feb. 27th 1850 is scrawled very lightly on the first page.

Warren, Vermont? Warren, Maine? Warren, Michigan? Who knows. Also Maria’s middle initial could be an L. or a C. It’s hard to tell.

I look through the pages, scanning recipes. I gather associates, locations, and dates. You know. Clues. Anything that might help me go down the “paper trail” in a somewhat efficient style.

Over the following pages, Maria instructs on preparations of Carolina rice pudding, dyspepsia bread, peach pickles, and more. A faded page describes exactly how to cure 12 hams. 12. Hams. Maybe she’s the butcher’s wife. Then again, maybe she’s the butcher. We don’t know.

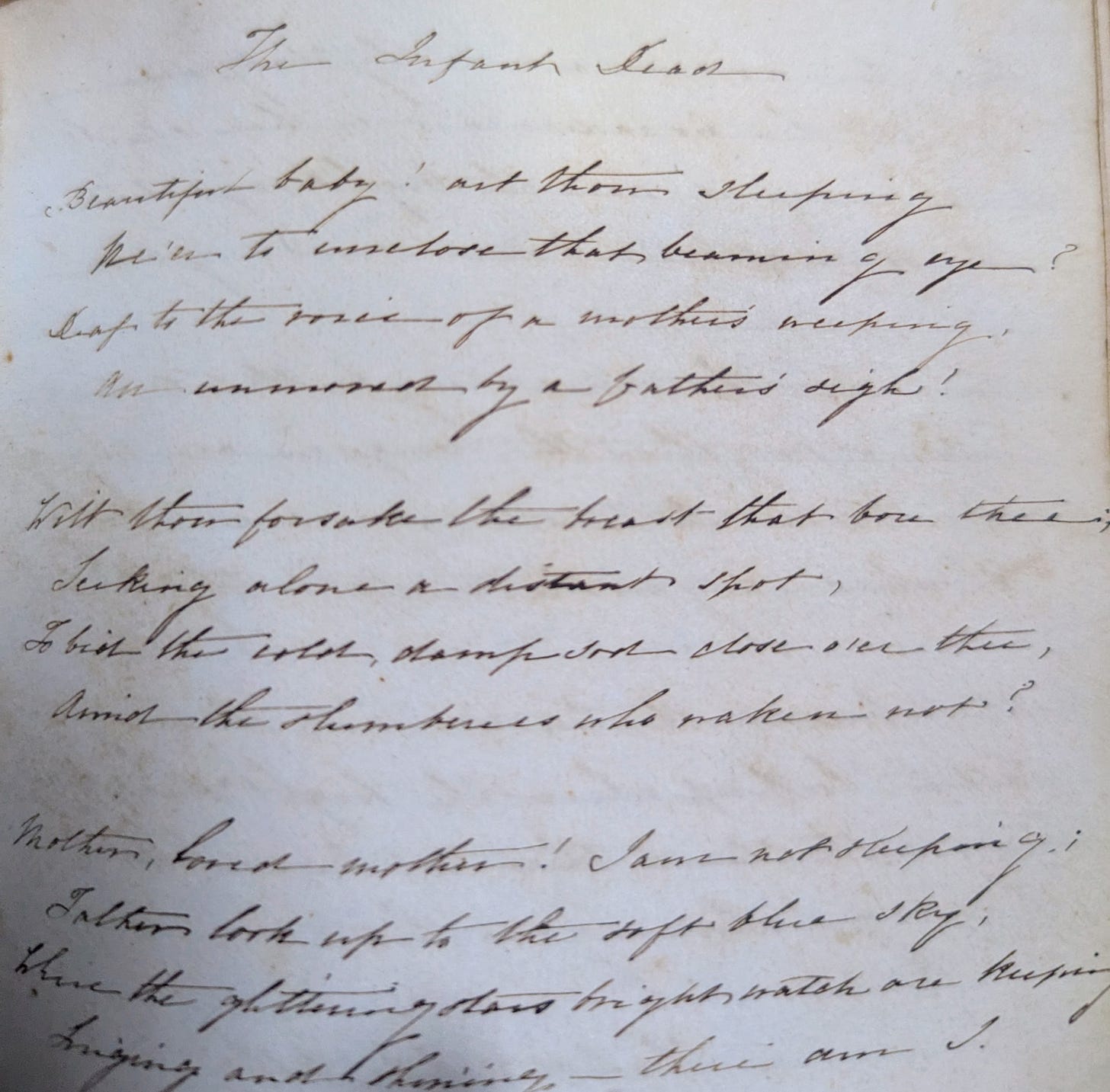

Recipes are delicately folded and pinned to the primary pages. I unpin and unfold and read. I go on like this for a while until I’ve run into the second half of the book which switches to poetry. Transcriptions of Longfellow and Charlotte Elizabeth [Tonna], and Caroline Bowles Southey span pages. I think I’m staring at words from her favorite poets until I start to look closer and realize I’m more likely staring at a moment in her life. They’re all, sadly, on one theme. Infant death.

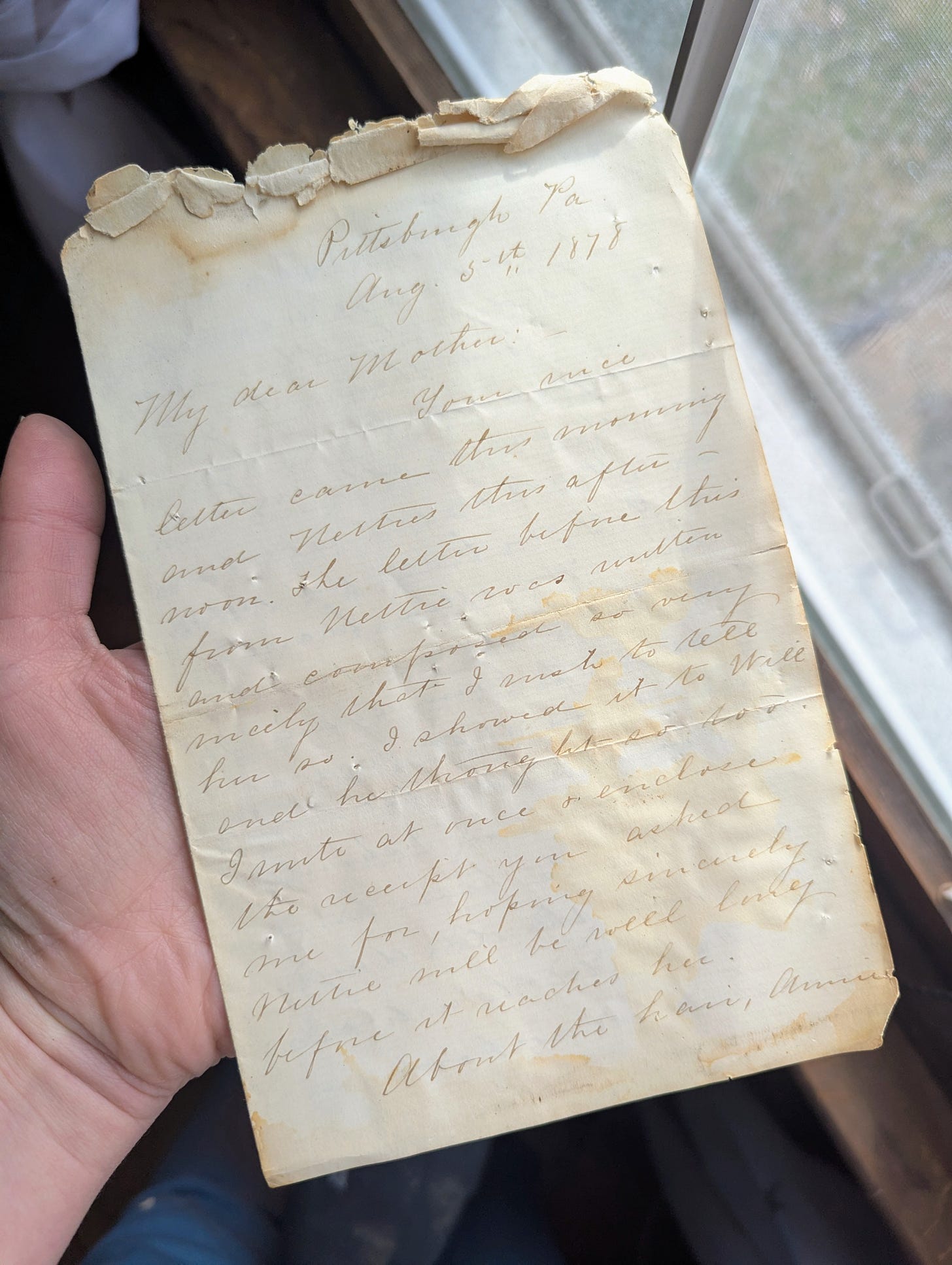

Finally, tucked into the back is a letter.

It’s addressed to Mother from Emmie. And herein lie a few more useful pieces of information. It’s just a letter about everyday things - borax in braids, new hoop skirts, a recipe receipt exchange - but she names names.

By the time I close the letter, I think I have enough to go sleuthing.

Maria Dubois lived in Warren ________ at some point between 1850-1880.

Maria may have had a child who died.

She had a daughter called Emmie and a daughter called Nettie. Probably nicknames.

Her daughter Emmie had a daughter named Emily.

Emmie had a relative, husband, or acquaintance named Will.

Emmie had a friend or relative named Annie McKay.

Emmie lived in Philadelphia in 1878.

Now, how many hams did Mrs. Dubois cure? Just kidding. But honestly. It looks like a convoluted word problem, doesn’t it? If you want to know how I solved this, subscribe. I’ll share stacks on research methods and add family history mysteries and puzzles over the months.

With this information in hand, I hit the archives. Here’s what I found.

Maria Coxe McIlvaine Dubois

Maria Dubois was born Maria Coxe McIlvaine in 1831 in New York. She was the daughter of Charles Petit McIlvaine (a clergyman and then Bishop of Ohio) and Emily Coxe. She married George W. Dubois (a clergyman) in 1848. There’s a lot written about George. He is fondly remembered as an Episcopalian Minister who liked to ponder Darwinism and peer through his telescope at the night sky. He was a chaplain for the 11th Ohio Infantry of the Union Army during the Civil War. He built a chapel in Keene Valley, New York, called St. Hubert’s.

Maria’s story is a bit tougher to grasp. As with many women of this time, they were just not chronicled as heavily as the men - their names most often found in association with those they married and cared for - and that’s where I began when I dipped into the databases to start to piece together her life. I followed George to find Maria.

While George was preaching, Maria was producing and running after the children. Eight children. She had her eldest Emily (Emmie) in 1849 when she was 18. They were living in Warren, Trumbull, Ohio. She received the recipe receipt book around that time. Then came George, Charles, Henry, Sarah, Henrietta (Nettie), Mary, and Cornelius. Her last child, Cornelius, was born in 1867, when Maria was 36 years old. That’s nearly 20 years of being pregnant on and off.

Most of her children lived to adulthood, except for Charles who did, indeed, pass away away at 8 months old in 1854. He’s buried with this grandfather in Ohio. Do you think those poems were for Charles?

During their child-rearing years, Maria and George moved around quite a bit for George’s mission, traveling from Ohio to Delaware to Michigan. Finally, they headed back to Maria’s birth state, landing in Keene and then Essex, New York. That, in case you don’t remember, is in the Adirondacks.

This region is known for their mountainous, forested territory, their lakes and streams, their farming, lumbering, and boat building. And it’s in this area where the Dubois family seems to have left their mark. Little pieces of their stories are scattered around public and private archival collections.

This portrait, for example, of Maria’s fifth child, Sarah (Sally), is from the Keene Valley Library Archives.

Sarah never married and would have been considered a spinster. Here, she’s pictured with an autoharp. Perhaps that was her only love. I wonder what she liked to play. This picture makes me think she could strum us a story, tell some mountain tales.

Another place we can find a few pieces of Dubois history is at the Historic Huguenot Street Archives in New Paltz, NY. Here we have family portraits, including one of Maria, herself. I’ve stared at this one for a while trying to pin a word or two on it. To me she looks tired, empathetic, worn, perhaps, but not unkind.

A few children’s portraits remain at Huguenot Street, too, including this one of her sixth child, Henrietta, otherwise known as Nettie.

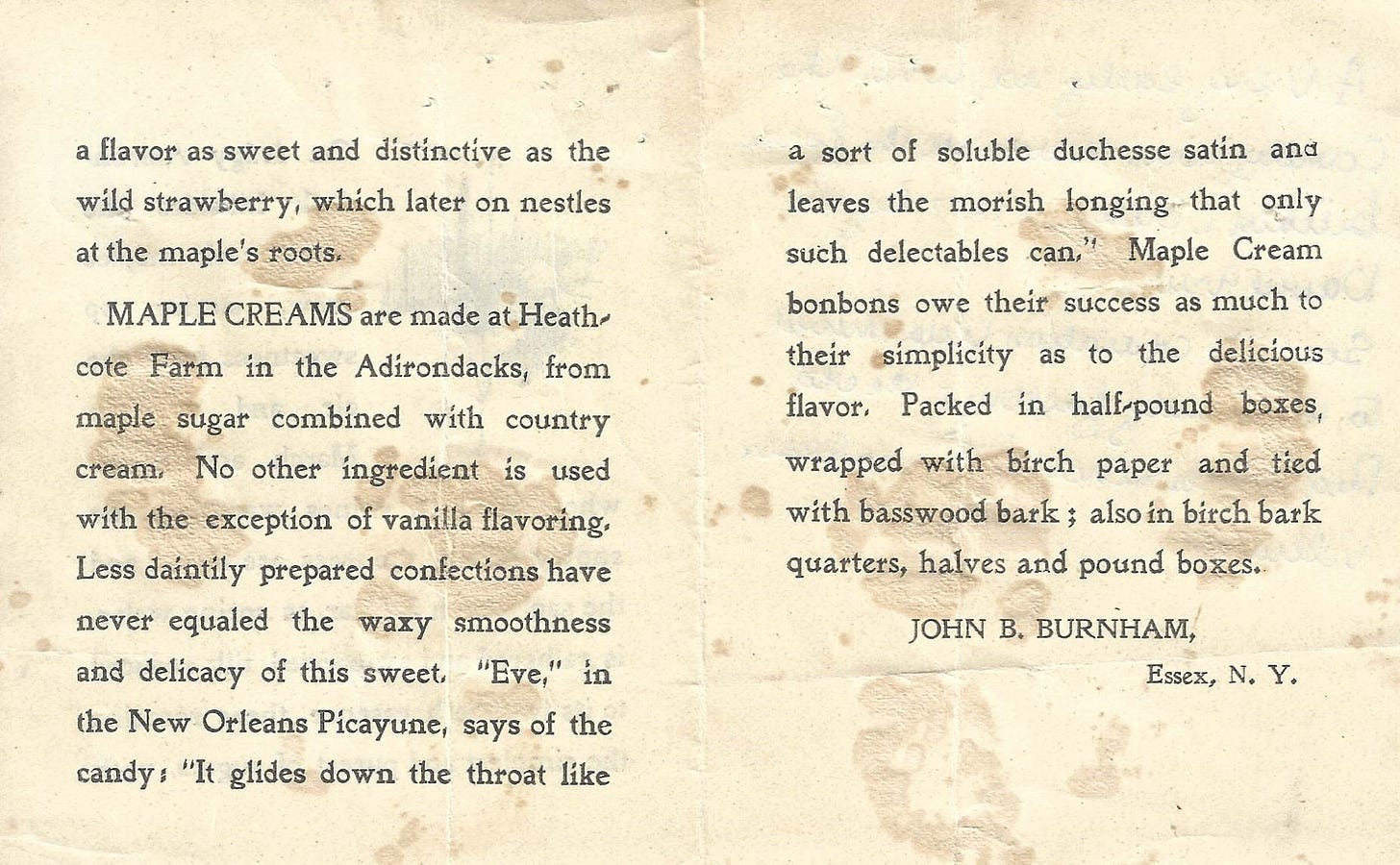

Nettie, grew up and married John Bird Burnham, a noted conservationist, adventurer, and entrepreneur. She created a candy called Adirondack Mountain Creams which were known and lauded far and wide. I scoured the recipe book to see if Maria had squirreled away the magic formula, but no dice. You’ll have to check in with the locals for that one - or attempt the one recorded here.

As I delved further and further through the archives, I was hoping to find more of the family papers. I was delighted that another archive did exist. It was passed from a family historian, Koert Burnham, to Maria’s descendant, Thedra, and her husband, John Nichols. I got to sit down and chat with John early on a Saturday morning.

As we passed family history notes back and forth, it became abundantly clear that they are knowledgeable on the subject and surrounded by family history. Not just papers, either. They have chairs and desks. They have portraits and clippings (some which have been seen here). They have advertisements for Nettie’s candy.

The family archive also includes a few letters from Maria. It’s such a robust collection one has to wonder how the recipe book missed the archival box. Maybe it was tucked away at the back of the kitchen cabinet. It eventually hopped a ferry and crossed Lake Champlain, landed in a bookseller’s hands, was passed to Ginger’s, and then to mine.

I’ll be sending it along, too. Back home, this time, so that it can join the family collection.

It’s a simple book, but it truly is a unique piece of Maria’s history. It tells us more than census records, probate records, and vital records. It’s brimming with family ties, community connections, and kitchen concoctions. There isn’t a page that passes that doesn’t have a special receipt given by a neighbor or acquaintance. Maria collected Muffins from Mrs. Goddard, Pumpkin Pies from Mrs. Douglass, and Charlotte Russe from Mrs. Willis. This reveals close friends and neighbors as well as gustatory habits, experiments, and goals. She preserved her own mother’s recipes for Soda Biscuits and Spruce Beer. These are cherished family heirlooms, perhaps even foods she ate while growing up. She recorded how to cure 12 hams. This certainly informs us as to what food she had available and how she might have endeavored to preserve it. It also tells us she was feeding an army- maybe in her own home, maybe as a right hand to the church. She knew how to conjure a feast. And then, of course, there is the poetry. It hints at a deep loss, a vulnerable moment written in her own hand.

Even though we’re far removed - by 170 years - we can still see the dance and the exchange. Food and letters passed from hand to hand and heart to heart. We see pieces of her life, her family, and her kitchen, largely because she took the time to write. She scribbled, reflected, and collected.

As we embark on the holiday season, we too will share meals, recipes, and letters. We’ll capture images and reflect on the closing of the year. Let’s take a cue from Mrs. Dubois and make sure we put some of it in pen and ink. Who knows where it will go.

Finally, since I’m holding the cordial, I might as well be the first to make a toast. As we near the end of 2024 and look to the new year, whatever it brings, let’s do as Mrs. Dubois suggests: put a good old spirit to it.

If you read all the way to the bottom of this post you obviously like vintage cookbooks and family history. Please subscribe! Free subscribers will receive occasional family history posts just like this one. Paid subscribers will receive monthly stories just like this one, as well as bi-weekly tips and tricks on genealogy and family history research skills.

Paid subscriptions help me with ingredients, out of state research expenses, graphic design software, and the purchase of records like birth, marriage, and death.

This blog post would be impossible without the dedication and staff at many local repositories. Historical images were pulled from the New York Public Library Digital Collections and New York Heritage. I also conferred with the Essex Town historians John Noble III and Todd Goff. Likewise, a huge thanks to the reference staff at the Historic Huguenot Street Archives. Their willingness to delve into their physical archive saved me hours of driving and enlightened me as I explored Maria and her family’s history. This post also would not be possible without other family historians. Thanks so much to John and Thedra Nichols for diving into the family archives and taking the time to chat with me about family history bright and early on a Saturday.

Any mistakes, misspellings, or historical misinterpretations are wholly my own.

I love how you’ve spun genealogy with the recipe finds. So excellent. Where did you originally find the recipe book?

Excellent!